Examining Bias and Representation in the Media

Overview

About This Lesson

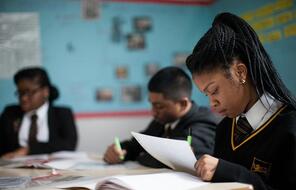

This is the second lesson in a unit designed to help teachers have conversations with students about media literacy in a critical, reflective and constructive way. Use these lessons to help students reflect on the changing media and information landscape; understand how this landscape impacts individuals, communities and societies; and consider how they can thoughtfully and responsibly engage with content they encounter online and in print. This learning can also help them become conscientious content creators. Supporting students to develop as critical consumers and creators of information is vital for their well-being, their relationships and our democracy.

This two-part lesson is a means of helping students understand how biases can manifest in media content and consider the impact of media representation. In the first part of the lesson, students consider the difference between fact and opinion, explore how to detect bias in language, and reflect on the power of language. Then, in part two of the lesson, students consider media representation, exploring how stereotypes are used in the media and the consequences of this. They begin by considering how a group to which they belong has been depicted in the media. They then reflect on the impact that stereotypes can have on how people view themselves, and how they view and treat others. Following this, they are informed about the relationship between stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination: prejudice occurs when we form an opinion about an individual or a group based on a negative stereotype. When prejudice leads us to treat an individual or group negatively, discrimination occurs. With this understanding they consider media content examples that contain stereotypes and/or prejudicial attitudes, and consider the impact that such content can have on those who view it. They then reflect on what can be done to challenge stereotypes.

We recommend that you revisit your classroom contract before teaching this lesson. If you do not have a class contract, you can use our contracting guidelines for creating a classroom contract or another procedure you have used in the past.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before teaching this lesson, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Lesson Plan

Part I Activities

Part II Activities

Extension Activities

Materials and Downloads

Examining Bias and Representation in the Media

Introducing Media Literacy

Understanding the News

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand