Understanding the News

Overview

About This Lesson

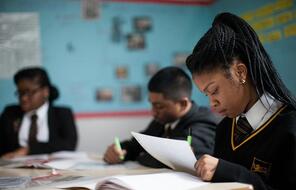

This is the third lesson in a unit designed to help teachers have conversations with students about media literacy in a critical, reflective and constructive way. Use these lessons to help students reflect on the changing media and information landscape; understand how this landscape impacts individuals, communities and societies; and consider how they can thoughtfully and responsibly engage with content they encounter online and in print. This learning can also help them become conscientious content creators. Supporting students to develop as critical consumers and creators of information is vital for their well-being, their relationships and our democracy.

This two-part lesson helps students develop as critical consumers of news content by encouraging them to think about the purpose of the news, whether or not it is impartial and independent, and about their own consumption of news media.

In the first part of the lesson, students reflect on what the news is and the purpose it serves, before thinking about the benefits and challenges of keeping up with the news. These activities are followed by looking at news values and thinking about what makes a news story newsworthy. In the second part of the lesson, students explore the ownership and political bias of different news sources, reflecting on the impact that these can have on news content. They then review headlines to understand how bias can manifest in the news, before comparing two articles, one from a tabloid and one from a broadsheet. They finish by summarising the differences between the tabloid and the broadsheet articles and their impact on the reader, and thinking about how they can apply what they have learnt in the lesson to their news consumption habits.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before teaching this lesson, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Lesson Plans

Part I Activities

Part II Activities

Extension Activities

Materials and Downloads

Understanding the News

Examining Bias and Representation in the Media

Exploring the Impact of Social Media

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand