Agency and Action

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- English & Language Arts

Grade

6–12- Culture & Identity

Overview

About This Learning Experience

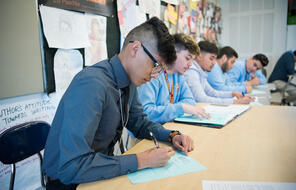

Part of being human involves facing choices and making decisions, both independently and in concert with others. Sometimes these choices and decisions are of little consequence; other times they have a large impact on our lives and quite possibly the lives of others, such as family, friends, or members of the community. When we call students’ attention to the concept of agency, both in literature and in life, we can help them understand that they are not only acted upon: they themselves, in a variety of ways, are actors in their lives and their communities. We can also provide opportunities for students to examine the societal forces that may play a role in increasing or limiting an individual’s agency to make decisions, take action, and have control over things in their lives

The following activities support students in analyzing key moments of decision-making in the text in order to explore a character’s agency and the societal factors that influence their decision-making process. If, as philosopher George Santayana has written, art provides an imaginative rehearsal for life, opportunities for students to examine complexities of the human experience through literature can help them to develop the tools they need to reflect on their own lives and to recognize the impact of their choices.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before using this learning experience, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Procedure

Activities

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Download the Files

Get Files Via Google

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand