Voice and Choice in Literature

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- English & Language Arts

Grade

6–12- Culture & Identity

Overview

About This Learning Experience

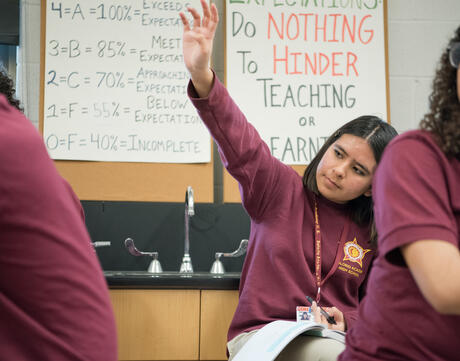

Many ELA educators are likely familiar with Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop’s metaphor that literature can work as a “mirror” to reflect and affirm a reader’s identity and as a “window” that enables a reader to experience the perspectives and beliefs of those who may differ from them. 1 Not only is this approach identity-affirming, it is also engaging and broadens students’ thinking about themselves and others.

In addition to reading widely, students benefit from opportunities to look critically at the texts they choose and the ones chosen for them in order to analyze the perspectives, voices, and representation included in and missing from these stories. Through this process, they can come to understand that there are different perspectives that the author deliberately constructs to convey what they want the reader to think about or know. In a similar way, students make choices in the stories they tell and how they tell them.

The following learning experiences provide students with opportunities to evaluate texts in order to identify the perspectives that are represented and to see if there are other perspectives that they should take into consideration before reimagining their own perspective into the text.

- 1Reading Rockets, “Mirrors, windows and sliding doors,” YouTube video, 01:33, January 30, 2015.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before using this learning experience, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Procedure

Activities

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Get Files Via Google

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand