Exploring Identity in Literature and Life

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- English & Language Arts

Grade

6–12- Culture & Identity

Overview

About This Learning Experience

Adolescence is a pivotal moment in the process of becoming in a young person’s development, and the students in your ELA classroom are deeply invested in exploring their own identities. The literature they read and the stories they write and tell in school are an important part of this process and can help them make sense of what they are feeling and experiencing.

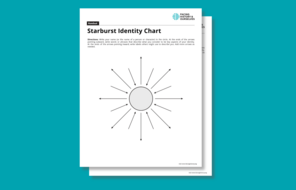

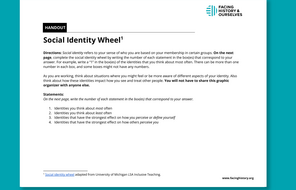

The following learning experiences help students explore the complexity and fluidity of identity, both in the world of the text and in their own lives. To help students engage with this complexity in progressively deeper ways, we have provided four learning experiences, starting with individual identity and then moving outward to help students consider their relationship to place, other people, and society. Taken together over the course of a unit or year, these learning experiences can help students understand that identity development is a complicated, ongoing process, and while it can be difficult and requires courage, there is power and agency in understanding the factors that make them the unique individuals that they are, as well as value in making space to learn the stories and experiences of those around them.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before using this learning experience, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Procedure

Activities

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Download the Files

Get Files Via Google

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand