What Is a Hate Crime and How Do Hate Crimes Impact People?

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- Social Studies

- Human & Civil Rights

- Racism

What Is a Hate Crime and How Do Hate Crimes Impact People?

Download a PDF of this resource for free

This explainer was created in partnership with the Office for the Prevention of Hate Crimes (OPHC), part of the New York City Mayor's Office of Criminal Justice and Mayor’s Community Affairs Unit. A PDF version of this Explainer is available to download at the bottom of the page.

A set of mini-lessons designed to help teachers explore the issues raised by the explainer in their classrooms will be available in late November 2023.

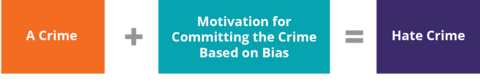

What Is a Hate Crime?

Under the law, the definition of a hate crime is: 1

- 1US Department of Justice, “Learn About Hate Crimes,” accessed September 25, 2023.

In other words, a hate crime must include both a crime and hate.

A crime can include property damage, assault, or murder.

In this context, hate means that the perpetrator (the person who commits the crime) chooses the victim (the person or group they target) because they believe the victim has certain characteristics or a certain identity.

Federally Protected Characteristics

Under federal law, hate crimes are crimes that are committed because of the victim’s:

- Race - any one of the groups that humans are often divided into based on physical traits regarded as common among people of shared ancestry

- Color - skin pigmentation other than, and especially darker than, what is considered characteristic of people typically defined as white

- Religion - a personal set or institutionalized system of religious attitudes, beliefs, and practices

- National Origin - national ancestry, parentage

- Sexual Orientation - a person’s sexual identity or self identification as bisexual, straight, gay, pansexual, etc.

- Gender - the behavioral, cultural, or psychological traits typically associated with one sex

- Gender Identity - a person’s internal sense of being male, female, some combination of male and female, or neither male nor female

- Disability - a physical, mental, cognitive, or developmental condition that impairs, interferes with, or limits a person’s ability to engage in certain tasks or actions or participate in typical daily activities and interactions 1

Hate Crime Laws

The federal government has hate crime laws, and most states do as well. The characteristics protected by state laws vary. For example, New York includes age in addition to all the characteristics listed above, while Alabama includes only race, color, national origin, and disability.

Hate crime laws usually act as penalty enhancers, meaning that someone convicted of a hate crime gets a stricter punishment than someone who commits a similar crime but is not motivated by bias.

Other Acts of Hate:

Some actions that are motivated by hate do not meet the legal definition of a hate crime, but these acts of hate are still harmful to victims.

For example, hate speech includes words or symbols that are intended to degrade, humiliate, or spread hatred against an individual or group of people because of their characteristics or identity. Because speech is protected by the US Constitution unless it causes immediate danger, most hate speech is legal. However, even when it is allowed by the law, it can still hurt the people it targets. Hate speech can also make it more likely that people will commit hate crimes.

REFLECT

- According to what you learned, what is the difference between a hate crime and other types of crime? For example, what would be the difference between property damage that is a hate crime and property damage that is not?

- Why do you think hate crimes are punished differently than other crimes?

- 1The definitions in this list are from Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary.

How Do Hate Crimes Impact People and Communities?

- Two men describe their reaction to having their gay pride flag burned outside of their home in Omaha, Nebraska, in 2015: “Had the man who burned our gay pride flag burned our Husker [football] flag, we would have still called the police—but we wouldn’t have felt as threatened . . . We wouldn’t have wondered ‘what’s next?’ What became so clear to us after Saturday night, is that the intent really does make a difference. Seeing him waving that burning symbol of a controversial, and inherent part of our being(s) as a minority, in front of our house as a clear message, made it scary. It made it an attack as opposed to a prank.”

1

REFLECT

Why do you think the two men said they would be less afraid if the perpetrator had burned a sports flag instead of their gay pride flag? -

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, a hate crime “is more than an assault on the victim’s physical well-being. It is an assault on the victim’s essential human worth. A person who has been singled out for victimization based on some group characteristic—such as race, religion, or national origin—has, by that very act, been deprived of the right to participate in the life of the community on an equal footing for reasons that have nothing to do with what the victim did but everything to do with who the victim is.” 2

REFLECT

How can hate crimes make it difficult for the victims to feel like full participants in their communities? -

Zainab, a Muslim woman, describes her reaction to hearing about hate crimes targeting other Muslims: “It does affect my behaviour . . . Because I become more fearful and would avoid going to certain places that I feel might be a risk to my safety. And especially within certain times, I would avoid walking within those areas.” 3

REFLECT

How can hate crimes impact people who were not directly targeted but do share an identity with the victim?

- 1Quoted in Phyllis B. Gerstenfeld, Hate Crimes: Causes, Controls, and Controversies, 4th ed. (Sage Publications, 2017), 16.

- 2Amicus curiae brief of the American Civil Liberties Union, Wisconsin v. Mitchell, 1993, cited in Gerstenfeld, Hate Crimes: Causes, Controls, and Controversies.

- 3Mark A. Walters, Jenny L. Paterson, Liz McDonnell, and Rupert Brown, “Group identity, empathy and shared suffering: Understanding the ‘community’ impacts of anti-LGBT and Islamophobic hate crimes,” International Review of Victimology 26 (issue 2): 143–62.

What Do We Know about Hate Crimes?

Collecting data on hate-motivated crimes is difficult:

- Fewer than half of all hate crimes that are committed are reported to the police. 1 Some of the reasons why hate crimes aren’t reported include:

- The victim fears the perpetrator will retaliate against them.

- The victim does not believe that the police will take action.

- The victim does not have enough evidence that the perpetrator was motivated by bias.

- The victim does not know that they are the victim of a hate crime.

- The FBI collects statistics on hate crimes, but thousands of law enforcement agencies across the country either do not report data to the system or report zero hate crimes. 2

While collecting information is challenging, the overall number of hate crimes appears to be increasing in the United States. 3

Hate crimes targeting a specific group of people almost always spike after the spread of negative news or conspiracy theories involving that group of people. For example:

- Hate crimes targeting people who were perceived as Arab or Muslim increased after 9/11 because these groups were falsely blamed for the attacks.

- Hate crimes targeting people who were perceived as Asian increased during the COVID-19 pandemic because they were falsely blamed for spreading the illness.

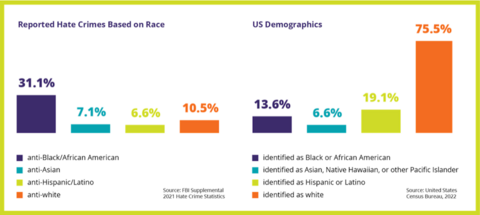

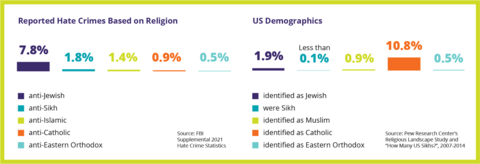

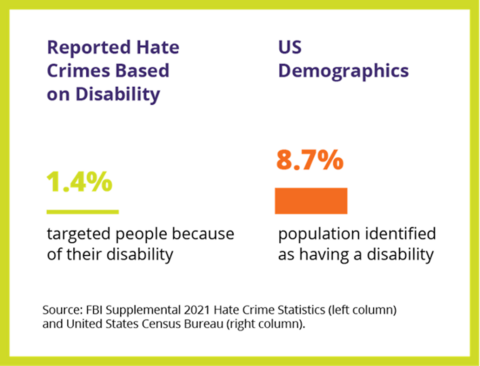

Hate Crime Statistics

The figures on the next page show data reported to the FBI on hate crimes committed in 2021 or 2022, compared to data on the percent of adults in the United States who identify with each characteristic. The comparison can help you see which groups are overrepresented or underrepresented in hate crimes data. Keep in mind that most hate crimes are not reported to the FBI, so these numbers do not paint a complete picture. 4

- 1Phyllis B. Gerstenfeld, Hate Crimes: Causes, Controls, and Controversies, 4th ed. (Sage Publications, 2017), 16.

- 2Gerstenfeld, Hate Crimes, 16.

- 3Brian Levin with Kiana Perst (courtesy of the Network Contagion Research Institute), Analisa Venolia, and Gabriel Levin, “Report to the Nation: 2020s – Dawn of a Decade of Rising Hate,” Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism, California State University San Bernardino, August 4, 2022.

- 4The following page describes the types of hate crimes and characteristics the FBI collects data on: https://www.fbi.gov/how-we-can-help-you/more-fbi-services-and-information/ucr/hate-crime.

What Do We Know about Perpetrators of Hate Crimes? 1

Nearly two-thirds of hate-crime assaults are committed by people under the age of 25. While most people who commit hate crimes are not members of hate groups, they are often influenced by the hateful ideas that these groups spread.

The researchers Jack McDevitt, Jack Levin, Jim Nolan, and Susan Bennett divide hate crimes into four different types, depending on what motivates the people who commit them. Hate crimes sometimes fall under more than one of these categories. The following is a description of the categories they developed.

- Type 1:

The most common type of hate crime is committed by a group of perpetrators, often teens or young adults, who are seeking excitement and to feel momentarily powerful. They select victims from a different identity group that they believe are vulnerable. According to the researchers, this type of hate crime can involve the following people:

- A “leader” who instigates the crime and may demonstrate more bias than the other group members

- A “fellow traveler” who participates in the crime

- An “unwilling participant” who does not actively participate in the crime but does not attempt to stop it

- A “hero” who attempts to stand up against the crime and stop it

- Type 2: The perpetrators of this type of hate crime believe that the victim is invading “their” space or taking resources that should be reserved for their own identity group. The perpetrators may be influenced by conspiracy theories or hate speech and are often teens or young adults.

- Type 3: The perpetrators of this type of hate crime believe that a hate crime was committed against their own identity group. They seek out a victim from the group they believe was responsible. The perpetrators may be influenced by conspiracy theories or hate speech and are often teens or young adults.

- Type 4: This type of hate crime is the least common but most deadly. Perpetrators believe that they are “crusaders” and are deeply committed to their prejudiced beliefs. They seek to eradicate the group they target and often kill multiple people at once. The perpetrator usually commits the crime alone but is often influenced by—or a member of—a hate group. These perpetrators are usually young adults or adults.

REFLECT

- What do you think about the finding that a large proportion of hate crimes are committed by young people acting in groups? Why do you think that might be

- How do you think efforts to prevent hate crimes might be different depending on what type of hate crime these efforts seek to prevent?

- When do you think people are more likely to be “heroes” and stand up against a hate crime? When do you think they are less likely to stand up?

- 1The information in this section is from the book Hate Crimes: Concepts, Policy, Future Directions, ed. Neil Chakraborti (New York: Routledge, 2015).