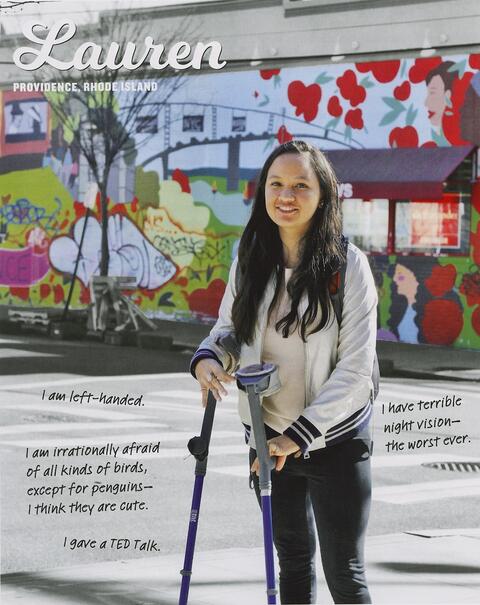

Lauren from Providence, RI

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- English & Language Arts

- Culture & Identity

As a kid, I thought very little about identity. I went to a very traditional Catholic school through eighth grade, and there was no discussion about identity. There was an assumption that I would perform well because my mom is Chinese. My mom always contacted my teacher to check on how I was doing, so she was stereotyped as a “tiger mom.” But wouldn’t any mom check on a daughter with a disability?

In high school, I took Mandarin and took a class trip to China. I was super excited. I had never been, and I always wanted to go. When I got there, I found out that, because of the one-child policy in China, if a family, especially in rural parts, had a kid with a disability, they usually sent you down a river. Literally down a river. They didn’t want their one child to be disabled. I was heartbroken. My mom came from Hong Kong to the United States with this mentality, and then she had me.

I was born with cerebral palsy. It’s a permanent disability. I have very limited ability to participate in normal, everyday things. I could never run around during recess. I could never go to summer camp.

People with disabilities are perceived as “crippled”—a word used way too often—as not able to be independent, productive members of a community. At the same time, I had to fight the stereotype of being a girl and “fragile.” I was never taught about feminism. “Feminism” was a bad word; it meant being a man-hater. I was never ladylike enough for my family. When girls got into fights, they would immediately go on social media and write a cryptic, passive-aggressive Facebook status like, “Oh, good friends come and go.” That’s how girls were expected to be—fragile, catty, mean, weak—and I was not having any of it.

I never really realized that I had a permanent disability until I was ten or eleven. I had been doing tons of physical therapy, and I thought that if I just kept working at it, then one day, it would be gone. Once I made that distinction, I began to think about what ability really means. I began to see things around me that were ableist. For example, in our chemistry room, there was a poster that had braille at the top and bottom and read, “Don’t forget to wear goggles. You don’t want to have to read braille!” So, what are you saying—that it’s a punishment to be blind?

I’m originally from New York City, and there are hundreds and hundreds of subway stations 1 across the five boroughs, but so few of them have elevators. People with disabilities are by far the largest minority in the world and the most underrepresented in everyday life. So the fact that almost none of the subway stations in New York City are accessible to us is a problem.

How are you expected to take a stand for something if you literally can’t stand? Think about the Women’s March. As much as I wanted to go, I couldn’t. There are people everywhere storming the streets—it just wouldn’t be safe for me. I couldn’t keep up with the crowd.

Part of the reason I am here today, though, is that we had a lot of socioeconomic privilege. I’m very fortunate, since I had so many medical problems, that my parents were successful, retired young, and were able to be full-time parents. But I didn’t feel I actually got to exercise that privilege. For example, after-school activities would never accept me. That intersectionality between ability and privilege has always been a conflict.

Being comfortable talking to people with disabilities adds visibility. Because the more you don’t talk about it, the more you don’t ask, the more you use softer words like “handicapped,” the more invisible our stories and experiences become. I don’t mind when my friends ask, “Lauren, are you disabled?” I don’t take offense to that, because it’s true: I do have disabilities. Just don’t be like “Oh. What happened? What’s wrong?” assuming that something happened to me, when in reality, I was born with it. 2

- 1Of the 472 subway stops in New York City, 80 percent are inaccessible to persons with disabilities as of 2017.

- 2From Winona Guo and Priya Vulchi, Tell Me Who You Are: Sharing Our Stories of Race, Culture, and Identity (New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 2017), 86–88. Reproduced by permission of TarcherPerigee, an imprint of the Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.