Breadcrumb

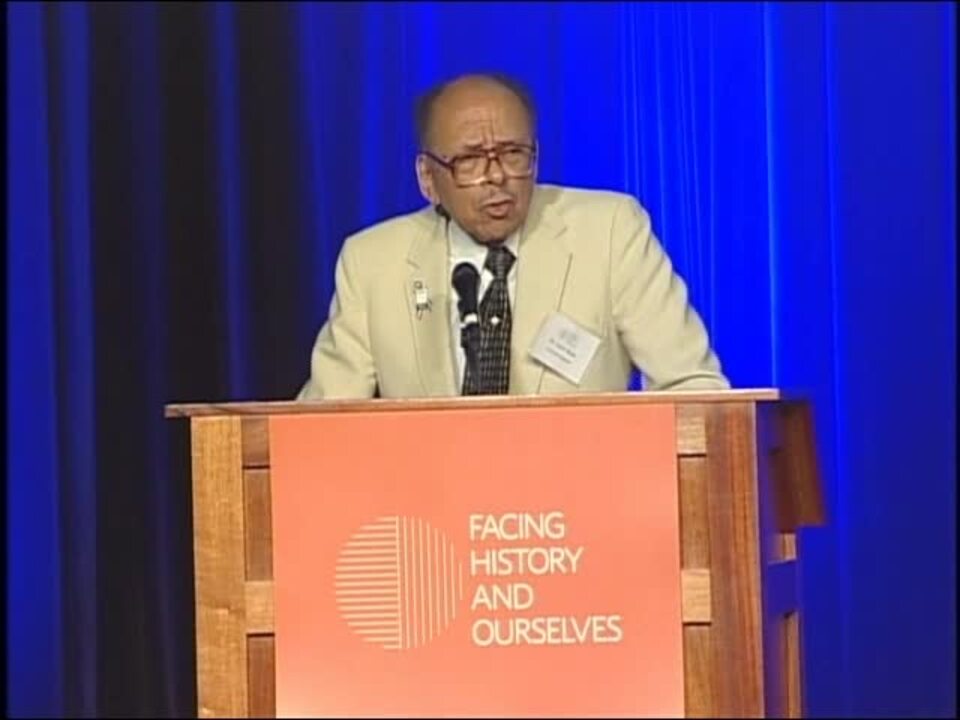

I Had Come Face to Face with Evil: Leon Bass Talks about his Experiences of Racism

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- The Holocaust

- Racism

I Had Come Face to Face with Evil: Leon Bass Talks about his Experiences of Racism

[APPLAUSE]

Wow. I thank you very much, my brother-- [CHUCKLES] --for walking into that class in 1951 50 years ago, bringing with you a love of learning and still sharing that with so many today. I thank you. I thank you.

But I'm here today to speak to you about experiences I've had that relate to Facing History and Ourselves-- experiences that were good, and some that were not so good. But we learn from those experiences if we work hard at it, so I want to talk to you about racism, antisemitism, and the Holocaust.

All three impinged on my life and caused me to think and feel as I do, and I want to share those thoughts and feelings with all of you here this evening. It all began for me back in 1943 when I completed my high school education. But when I came out of high school, our country was fighting a war.

So I did what so many young men were doing at the time. I volunteered to be part of the United States Army. But it was that decision that brought me face-to-face with institutional racism. It happened on the day that I was inducted into the service.

I went down to the induction center in Philadelphia-- excuse me-- with some of my friends. And they happened to be white. When we got to the door of the induction center, there was a sergeant standing there. He took one look at me, and he said, go this way.

He looked at my friends, and he told them to go this way. Now, that was done, because back in 1943, all of our armed forces, the entire military, was segregated. My country, our country, practiced and promoted institutional racism.

And by doing that, my country was saying to me, Leon, you're not good enough. No. You're not good enough to serve the country with white soldiers. So they separated me from my friends.

I was sent down into the deep South for my basic training. I went down to places like Georgia, Mississippi, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas. In all of these places, every one of them, the people-- the people that I'm supposed to protect and defend-- these same people let me know every day in so many different ways that they, too, thought I wasn't good enough.

I wasn't good enough in Macon, Georgia, to get a drink of water at a public water fountain. I wasn't good enough in Texas to get a meal in a restaurant. And in Mississippi, when I took a seat on the bus, took a-- got aboard the bus, I looked up and I read the sign.

The sign said, colored must be seated at the back of the bus. Well, look, I go to the back of the bus. But when I get back there, I discover that every seat that should have been available for me to use-- all of those seats were already taken.

So on that day, my friends, I stood up for more than 100 miles, and I looked at empty seats on that bus that I was not permitted to occupy. They said, I wasn't good enough. What a damnable experience to have when you're 18 years of age, and you have volunteered to serve your country.

But there was nothing I could do about that situation in 1943 except to keep my pain inside. Then, my unit, 183rd engineer combat battalion, had overseas duty. So we went across the Atlantic Ocean to England, then we left England and went into France.

And we got off the ship when we got to France and drove up to a small town. And we parked outside of the small town, and we had to wait for orders-- orders that would tell us what our responsibility was going to be in the war. And this was 1944.

The weather was severe, temperatures well below zero, snow everywhere. But we waited, and finally, the orders came down and said that our unit, 183rd engineer combat battalion, would be attached to the Third Army under the leadership of General George Patton. But just at that time, things began to happen-- things which we knew very little about.

The enemy, in a last desperate attempt to try to win the war-- that enemy counterattacked. They hit us hard. They did it at a time when the weather was severe. Skies were overcast. We had no support from our Air Force.

And they pushed our front lines back, back. They created what we call a bulge in our front lines. And I'm quite sure all of you who are conversant with history know that I'm talking about the Battle of the Bulge.

We went into this battle that my unit had as its first commitment. We were told we had to go into Belgium. We had to go to a small town, a place called Martelange. Martelange was small, but in the town, there was a bridge.

That bridge had been destroyed completely by the enemy, and it became our responsibility to rebuild it. And this, we had to do, because you see, further up the highway, about another 15 kilometers, there was another small town called Bastogne. And in Bastogne, there were soldiers.

These were American soldiers. Some of them were members of the 101st Airborne Division. They had been trapped in that town. The enemy was all around them. Their lives were in jeopardy. They needed support badly.

So General Patton and others began to get the resources together-- tanks, guns, men, ammunition. They were going up there. They were going up to help those soldiers, help them to defeat the enemy.

But in order for them to get up there, many of them would have to cross this bridge in Martelange. So we had our work cut out for us. We had to rebuild that bridge. So we began to work.

In spite of the weather, we worked. In spite of the shelling of the 88 howitzers of the enemy, in spite of the airplanes coming over every day, strafing machine gun bullets and trying to bomb the bridge, in spite of landmines that were everywhere, we worked on the bridge. And we finished that bridge. We finished it on time.

And all of those resources-- men, tanks, guns, whatever-- crossed the bridge. They went up to Bastogne. And they helped those soldiers defeat the enemy. Oh, my friends, that was a wonderful experience for me.

It was a glorious day for all of us. But you must remember this. Whenever you fight a war, quite often, you pay one heavy price for glory. And I found out about that one day.

One day, I was standing in the snow alongside the road, and I was watching these trucks go by. These were grave registration trucks with the bodies of American soldiers piled high, atop one another. And I stood there, and I looked at that, and I said to myself, Leon, what are you doing in this place? You could end up that way.

I began to question my wisdom for having joined the army. What are you doing here? What are you fighting for? Now, look, I asked that question because I had fast become an angry, young Black soldier, angry at my country. Because I felt my country was using me, abusing me, putting me out in harm's way to fight and maybe die, to preserve all those wonderful things that every American should enjoy.

And yet, my country was saying to me in so many different ways, Leon, you are not good enough to enjoy what you're fighting for. And that's what made me angry. But the war went on. My unit went with it.

We went all through France, Belgium, Luxembourg. We went into Germany. And one day, we were up near a place called Weimar. And it was at that time when we were setting up a camp, that the Lieutenant came over to me, and two others.

And I was in the intelligence reconnaissance section, and so he was my lieutenant. And he said, come with me. We followed him. We got to board the truck, but I leaned over and I said to him, sir, tell me, where are we going? He responded by saying, we're going to a concentration camp.

What? A concentration camp? I didn't know anything about concentration camps. In all the training they had given me, no one ever mentioned a concentration camp. But on this day in April in 1945, I was to have the shock of my life.

Because I was going to walk through the gates of a concentration camp called Buchenwald. And you've got to believe me when I tell you, I wasn't ready for that. Oh, no, I was totally unprepared for that kind of an experience. But I can never ever forget the day, that spring day in April when I walked through the gates, and I saw in front of me what I have come to know as the walking dead.

I saw human beings that had been beaten, starved, tortured, denied everything-- everything that would make life livable. There, they stood in front of me. They were skin and bone. They had skeletal faces with deep-set eyes.

The hair had been clean-shaved, and they were standing there in these ragged pajama-type clothing. Some of them were naked, and I could see the sores on their bodies that came from malnutrition. One man held out his hands. His fingers had webbed together with the scabs that come from the sores brought on by the malnutrition.

I stood there looking at that, and I said, oh, no, no, no, what is all of this? Oh, look, I had seen death and dying, yes, but nothing like this. But then, suddenly, they began to move. They started stumbling forward toward me.

And as they did this, they began to speak. They were saying things in so many different languages, and I couldn't understand any of it. So I sort of backed away, but then I stopped. And I said to myself, my god, who are these people?

What had they done that was so terrible that anyone would treat them like this? I didn't know, honestly. I didn't know. But there was a young man. He was Polish, but he understood and he spoke the English language well, so he began to tell us about Buchenwald.

And he said, these people were Jews. They were Gypsies. They were Jehovah Witnesses. Some were Catholics. They were trade unionists, communists, homosexuals. Oh, he went on with a litany of groups that had been placed in the camp by the Nazis.

And I say to you this evening that in my judgment, the Nazis placed them there because the Nazis were saying, none were good enough. Therefore, they were not fit to live. They could be terminated, murdered. Wow.

I had never seen anything like this. But I know I wanted to see more. I needed to see more, so I walked about the camp. I went to a place where the men were asleep. We called it a barrack.

I opened the door, and I stepped across the threshold and closed the door. But I could go no further. You see, the odor, the stench that comes from death and human waste-- it was overpowering. It was awesome.

I stood there, holding my breath. I knew I had to leave, so I turned, but before I could step away, I looked down, and there on the bottom bunk was a man. An emaciated skin-and-bone human being-- he was on a bed of filthy straw and rags.

And he was trying so desperately to look at me with that skeletal face and those deep-set eyes, but he was so weak. He had been starved for so long. It was a struggle for him just to look up at me.

But finally, he did. He looked up at me. He said nothing. Nor did I. So I left that place. I went to another building that the gentleman had pointed out to me.

He said, I would find all parts of the human body in jars of formaldehyde. This is where I discovered that the Nazis did medical experiments on human beings in Buchenwald, often without any kind of anesthesia. And I saw, after the doctors would work on the part of the body they wanted, the surgeons, they would take it and put it in a jar and put on a label.

Well, I couldn't read the German, no. But I could see, and I saw it all-- eyes, ears, fingers, hearts, livers, kidneys, genitalia. All of it was there on a table nearby. I saw human skin-- human skin. Someone had done artwork on the skin.

There was a lampshade in that room, and it, too, was made out of human skin. My friends, that's enough to boggle your mind. But I saw it. I did. I went to another building.

I was told this is where they interrogated the prisoners. This is where they tortured them. I went inside, and I saw the blackened blood on the cement floor.

I saw the blood on those slabs, where they would put the victims. And on the wall, I saw the instruments of torture that they used. They were still hanging on the wall.

So now, I believed. I believe that the people evil enough in our society to do things like this to others. I'd been in the camp maybe five hours. And in all that time, I didn't see any children, so I asked the young man. I said, where are the children?

And he assured me that the children were in the camp, but I never saw them. Yet, on this day, when I was leaving this building, I saw the clothing of the little children-- the little children that didn't survive. Up against the wall, there were mounds of clothing, caps, sweaters, stockings, shoes.

For babies, there were little booties. I saw all of these things and more that belonged to the little children. But I never saw a child. Well, I walked past the dead and the dying, and got close to another building.

And as I got closer, I could see the dead bodies stacked up about 4 feet high. They stretched about from where I'm standing to that poster there. They were outside of the building called the crematorium.

I went inside, and I discovered six ovens. I walked over and looked into one, and I saw what was left of someone who had been placed there. I saw the man's broken-- I'm sorry. I saw his skull, blackened skull.

I saw his rib cage. I saw all the bones and the ashes. The young man said, on a given day, the Nazis would come with a truck and remove the ashes from the ovens. These ashes would be transported to a farm, and they would spread the ashes all across the farmland as human fertilizer.

That would enrich the soil, they thought. And in time, they could grow the food that would help them feed their army, the Wehrmacht. Well, by this time, I'd seen enough more than I want to talk about here this evening with you.

I had seen enough. My stomach was upset. So I walked away from my friends. I walked back to the gate where we had come in, and I stood there waiting for my friends to come.

But while I waited, I realized that I was not the same anymore. Something had happened to me. Remember, I'm this angry young soldier, angry at my country for what it had been doing to me, telling me I wasn't good enough.

But now, I could see a bit more clearly. My blinders came off. My tunnel vision dissipated. I now understood that human suffering is not relegated to just me. Oh, no.

That pain and suffering can touch all of us. Every one of us. But more than that, I knew that on this day, I had seen the face of evil. Yes, I knew of bigotry, prejudice, racism, antisemitism-- all of those things and more, I saw it.

I felt it when I was in my own country. And now, I saw what can happen. If we turn our backs, if we don't pay attention, if we don't be prepared, people can take over. We mustn't let that happen.

But the Nazi-- oh, they took that evil to another level. They came up with what they call a final solution. That meant they were going to get rid of everybody.

Now, I didn't know the enormity of what I had seen. I thought that Buchenwald was just one place in the whole scheme of things, but I found out later that places like Buchenwald had been replicated all across Europe and into Russia. And when I came home, I got the statistics.

12 million people. 12 million-- not soldiers. Civilians, babies, children, people who were infirmed in the sanitariums, the blind, the lame-- all of those people-- old people. All of them-- 12 million souls lost, because somebody said they weren't good enough.

Oh, my friends, I said, if I could ever get home again, I wanted to do something. I didn't know what I could do. I was just 20 years old. But I wanted to do something when I got home.

So I left that camp with my friends, got aboard the truck, and no one had said a word about what we saw that day at Buchenwald. The war ended. They sent me down to the Pacific until the war ended there.

And then, I came home, back to Philadelphia in Pennsylvania. My parents always thought that maybe I should go to college one day-- wishful thinking. But I decided I'll give it a shot.

I would go out to a place in Pennsylvania called Westchester, because I had what they call the GI Bill of Rights. And that bill said every soldier with an honorable discharge was entitled to certain benefits, and one of those benefits was a college education.

So I go out there. I walk into the registrar's office. I say, I'd like very much to be a student-- a student at your college. And he looked at me in a strange way and said, young man, you must go back to your high school and have them send us all a transcript.

I said, what's a transcript? He said, that's a record of all your grades that you've earned when you were in high school. I said, oh, I'm in trouble now. I had a good time in high school. I tiptoed through the tulips, finger popping, hey!

But now, I had to pay for it. But no, somebody up there liked me. I got a letter saying, Leon, you're accepted as a student at Westchester State Teacher's College. Wow. What a happy man I am, first one in my family to go to college.

But then, my happiness disappeared. You see, I found out that the face of evil was in Westchester. It was in the town. It was on the college campus.

You see, after I registered, I waited around. I wanted to find out what dormitory I was going to live in. Who was going to be my roommate? No. No, that wasn't going to happen.

I wasn't going to live in the dorm. I wasn't going to have a roommate. They had already decided that I wasn't good enough to live in their dorm and have a roommate.

That's hard to believe. Here it is, 1946. I spent three years of my life in the military. I risked everything. I laid my life on the line to keep those people in that town and on this college campus safe and secure.

And now, they're saying to me in 1946, Leon, you're still not good enough. Oh, my friends. I could stand up here tonight and tell you that I was angry, but that would be an understatement.

I was more than angry. I was furious. And I'd been reading a lot, and I read something that James Baldwin wrote when he said, "to be Black and in America is to be in a constant state of rage." Oh, I was fast approaching that, but I was lucky I had good parents.

My dad and mom sent me down and said-- my father said, son, don't go out to that Westchester running your mouth, thinking you alone can change the world. No. The priority for you now is to go out there and get an education. All those changes you're talking about-- they're going to come, yes. It's inevitable.

That's going to come. But right now, your priority is to get an education, because son, once you get that, nobody-- nobody can ever take it away from you. So I listened to my dad. I swallowed my pride. I kept my pain inside. I went inside the institution. I got my education.

They told me I had 25 minutes. I hope I'm not overdue. But anyway, one day, I went up High Street to the movies at a Warner Theater, bought a ticket, went inside, and gave it to the usher. Right away, he pointed to some steps-- steps that led up to a balcony.

He was telling me I wasn't good enough to sit down on the main floor. He should never have done that, no, sir. I walked past him. I walked into that movie, and I sat down in the middle on the main floor. That was my protest.

I was telling him and everybody else who would hear me, I'm good enough. Well, now, when you're upset, you do a lot of strange things, you know. And I'm sitting there, and my nerves took over.

And I'm saying to myself, Leon, you're not going to graduate from college. You're going to jail. And they would call the police in a minute. They would. But nobody came. Nobody came.

The movie ended. People got up to leave. So did I. But as I walked out, I looked around. I was waiting for the policeman to put their arm on me, but no one did.

I had a room in the town where I was living, so I walked back to my room. And every minute and every step, I kept getting taller and taller. I must have been 10 or 15 feet tall. I felt that way, because I had come face-to-face with evil, and I didn't become evil.

And that was the most difficult thing I'd ever done in my life. Believe me. But what a joy I had knowing I had done the right thing. 1949, I'm graduating from college.

I have a teaching job in Philadelphia. I'm going to teach in an all-Black elementary school. I had 49 youngsters in my classroom. 49 youngsters-- wall-to-wall children. They came every day. They would never stay home, any of them.

[LAUGHTER]

And oh, if ever you were a teacher, it's always that first year that you work so hard. And I did. I worked so very hard. But it was a joy, because it was something that I wanted to do.

And the kids would fight each other on the way home, like most kids do, and I used to get the notes from the parents about it. But I didn't know how I could solve that problem. They wanted to use violence to solve the problems, and I said, no, that's not the way.

But I didn't know what to do until the clarion voice of Dr. Martin Luther King came out of the Deep South, and I heard him say-- well, he wasn't talking to me, but I heard him. I heard him say, Leon, you can change things, but you don't have to be ugly to do it.

And he started talking about love and caring. And I said, that man is crazy. He wants me to love people who are going to kick me in my tuchus and do all kinds of things to me? No! I can't--

And Malcolm was speaking, too, Malcolm X. He was saying, don't bother anybody. But if they put their hands on you, send them to the cemetery. Ooh. Now, I had a choice.

That's what we talk about-- choices. I had a choice. But my parents prevailed, and I followed Dr. Martin Luther King. And I'll never forget that day on Sunday in 1943-- was that right? Yeah.

Went to Washington DC with 250,000 people. We marched on Washington. We went down there to tell the Congress and the world that we were good enough and it was time for things to change. And we waited out in front of the Lincoln Memorial for this giant of a man to come out and speak to us.

And I remember that summer day, when he came out, he stood before the lectern and raised his voice. He said, I have a dream. I have a dream that one day, people will be judged not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.

I have a dream, he said. And I stood there crying. Yes, I was crying. But all around me, people were crying, all kinds of people-- white, Black, Brown, Jews, Catholics. Oh, you name it. All of them were there, crying unashamedly. What a wonderful, beautiful day this was.

So I came back home, and I worked hard as a teacher. I became an elementary school principal in an all-Black school. And no, I'm wrong. I had a white janitor.

[LAUGHTER]

You caught it, didn't you? Then, they sent me to an all-white school, and I had a wonderful time there. But then, tragedy struck. Dr. King was assassinated. What a terrible time that was.

I guess people were thinking they lost the dream, because they'd lost the dreamer. That's not the way it was, but that's the way many people perceived it. But then, one day, I got a call from the superintendent of the school-- said, come to my office.

And I go down. He said, Leon, I have a high school that needs a principal, and I thought about you. Would you be willing to provide the leadership that school needs? And I looked at him, and I got very suspicious.

And I said, what's the name of that school, sir? He said it's the Benjamin Franklin High School. He could have stopped right there. He was talking about the toughest school in the city of Philadelphia.

There were no girls in the school. These were all young men, and they were bad. I mean, when I say, bad, I mean, bad-bad. Really bad. Gangs, all of that.

When I was going to school, they were bad. We played football against them. At the halftime, these gangs would run out on the playing field, turn around, and look at us and start cheering. If you win the game, we're going to win the fight.

Oh, my goodness. Needless to say, I never waited for the game to end. I left early.

[LAUGHTER]

But now, now, I'm the principal of the Benjamin Franklin High School. I put on my good shirt, tie, and I had my attache case. At that time, I had just joined the Society of Friends. I'm a Quaker.

And all that love-- I had an attache case filled with that love, and I'm going to change the world. No. When I got near the school and saw the crowd out on the front, out on-- blocking traffic on Broad Street, I said, why aren't they in class?

I didn't know they had a big demonstration at the Board of Education trying to get them to improve the quality of education in the schools. But it got out of hand. People were arrested and beaten. And here I come, change the world.

I started towards the door. I almost made it. But this fellow stood in front of me. He was big. And I looked at him, and he said, Mister, you the new dude they made principal at the school? Oh, boy.

[LAUGHTER]

I sort of started to laugh a little bit. I said, well, that's what they've been telling me. And he said, well-- fellow-- he started yelling. Fellows, he's here! He's here!

They'd never had a Black principal since the school's inception, and I was chosen. And they crowded around me, some of these gangs, big-- oh, I knew I was in trouble. And so they started saying, what are you going to do to make the school better? What's your plan of action?

I said, back off, fellows, give me a break. I just arrived here. And that's when a voice came out of the crowd. Mister, if you don't do something right away, we're going to burn this place down.

And he was serious. They were all serious. I had my work cut out for me. So I walked around the school, trying to get a handle on things, but I couldn't seem to do it until I heard a noise on the-- I looked in the classroom, and I heard this lady trying to speak to these young men.

And they were rude to her. They weren't listening. So I stepped to the door, and I found her. There she was. She wasn't a teacher. No. She was a visitor.

She was a survivor. She had survived one of the worst concentration camps in Europe. She came out of a place called Auschwitz, and on this day, she had come to the school to speak to these young men.

She wanted to share her pain, and they weren't listening. So I stepped right up front. I said, all right, fellas. Hold it. Cool it. Listen. What the lady's trying to tell you, all of that is true.

I know it is, because I was there. I saw it. Those young men got quiet. I know they did. And they listened to what she had to say. She shared her pain. She told them how she'd lost her grandmother, her grandfather, mother, father, three brothers, and a sister.

All had come in to Auschwitz. All went to the gas chambers. All of them ended up in those despicable ovens. So when it was all over, they listened. I know they did by the questions they posed.

Then, they came up and shook her hand and looked at the numbers that had been tattooed on her arm for identification purposes. And then, they did something that was out of character for them. They walked out of the classroom in silence.

And she turned to me with tears in her eyes. And he said to me, young man, you have something to say. You should be telling people what happened to you when you were down in the deep South and how they treated you and said you weren't good enough.

You should tell them what you saw when you went into that camp at Buchenwald. You have something to say. This was 1971. I've been speaking ever since.

I traveled all across the country and to Canada, all over, talking to people, telling them what I experienced, letting them know about the transformation in my life, and somehow, we can get a transformation. I hope not with some tragic thing that's going on, but so much of it is happening today.

The genocides are still going on. People are killing each other in the name of god. Yes. But somehow, we have to change that, and that's what Facing History is all about. It's here to change the hearts and minds, especially of our young people.

Get them away from bullying. Get them away from saying things to people just because they're different-- negative things, denigrating things. We have to do something.

And before we can do that, we must look in the mirror, and we must ask what we see there. What am I doing? What am I contributing? What is it I'm failing to do?

And when we do that, we should just not give our money. We give our energy, our minds, our commitment to stand up for what we believe is right. You say, well, that's not easy. No, it's not easy.

People will talk about you. They'll put you down, and they'll say all kinds of things about. If you talk too much, you might end up losing a job, yes. So you answer the question, is the price too high?

I don't think so. But I can't speak for you. I can only speak for me. You must answer the question, is the price too high? Then, you must dare to be a Daniel.

Dare to go into the den of evil. Dare to stand up and speak to people in a nice way. Disagree with them agreeably, but don't give tacit agreement by keeping silent. No.

So when you come to Facing History, bring your money. We want that. Yeah. But more than that, we want you. And that's what's important.

All these young people especially need you. Our hope for tomorrow is out there, those young people. We've got to do something to help them. I know they can call you all kinds of names. They can do all kinds of things, and you read about them in the paper. They're the worst people in the world.

But no, no, no, no. All of them are not. I know. I've been around to all these schools and colleges, and I know there's some wonderful young people out there who are just waiting for us. So let's join together again and do what we can for Facing History.

So let me close with the-- I've talked too long. I'm sorry. Words of James Baldwin, who said, and I quote, "either we love one another, either we hold to one another, or the seas will engulf us, and all the lights will go out." We, you and I, we have an awesome responsibility. We must keep the lights shining. Thank you for listening. Thank you very much.

[APPLAUSE]

I Had Come Face to Face with Evil: Leon Bass Talks about his Experiences of Racism

How to Cite This Video

Facing History & Ourselves, “I Had Come Face to Face with Evil: Leon Bass Talks about his Experiences of Racism,” video, last updated March 31, 2014.

You might also be interested in…

Developing Student Agency through History and Literature: Middle School Curriculum

Resources for Civic Education in California

Resources for Civic Education in Massachusetts

Pre-War Jewish Life in North Africa

Responses to Rising Antisemitism and Antisemitic Legislation in North Africa

The Holocaust and North Africa: Resistance in the Camps

The Holocaust and Jewish Communities in Wartime North Africa

10 Questions for the Past: The 1963 Chicago Public Schools Boycott

Why Is the Coronavirus Disproportionately Impacting Black Americans?

Voting Rights in the United States

The 1968 East LA School Walkouts

California Grape Workers’ Strike: 1965–66