Create a Textual Lineage

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- English & Language Arts

Grade

6–12- Culture & Identity

Overview

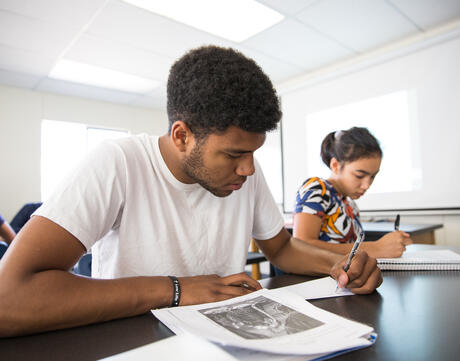

About This Learning Experience

In groundbreaking research that focused on providing African American boys with meaningful literacy experiences, Dr. Alfred Tatum developed the idea of “textual lineages,” or texts that have meaning and significance in our lives. 1 These might be texts that stay with us throughout our lives because they transported us to a magical place or showed us something magical about ourselves. Or perhaps they challenged us to think in new ways or to act differently. The stories in these texts resonate with us, and over time they become part of our own story. In literature as in life, characters can be impacted by the books they read, the poetry and music they experience, or a film they watch. These texts become part of the character’s identity—the story they tell about themselves and the story they lean on to help them understand others.

If your work of literature includes meaningful allusions to texts, the following learning experiences support students in considering the profound impact that the spoken and written word (as well as art and sound) can have on an individual’s identity and sense of self, and the way that our textual lineages can spark our minds, hearts, and imaginations.

- 1Alfred W. Tatum, “From Alfred Tatum on Literacy: (Re)Authorizing Literary Practices for African American Boys” (blog post), Coalition of Schools Educating Boys of Color (COSEBOC) website, November 2012.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before using this learning experience, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Procedure

Activities

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Get Files Via Google

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand