Breadcrumb

Colonialism and the Jews of North Africa

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Social Studies

- The Holocaust

- Racism

Colonialism and the Jews of North Africa

[MUSIC PLAYING]

So beginning in the early 19th century with the French incursion into Algeria, and what will become a brutal and violent occupation of land and people that actually unfolds over many decades, this inaugurates across North Africa an era of colonial control.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

It will unfurl in different places at different times. And the nature of colonial authority will be different from place to place. And this is very apparent when it comes to the Jews of the region. Because if we turn, for example, to the realm of colonial law, we can see that French occupying powers initiated different strategies for dividing, legally speaking, and ruling the populations of North Africa.

In the French protectorate of Tunisia, for example, the French decide that Jews, like Muslims, will be categorized as Indigenous people without the rights of French citizens. They are colonial subjects.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

And there, most Jews are treated like most Muslims, except there is a population-- and this is true across the entire region-- of Jews who actually have the protection of foreign powers. And this will come into play during the Holocaust.

By contrast, in Algeria, the French regime determines that it will extend at a certain point citizenship to the majority of Jews-- a right, an opportunity, a duty that is not extended to the many millions of Muslims in Algeria.

And again, one could look from place to place and compare and contrast strategies of colonial rule that take shape in North Africa. But here, I think is the main point to emphasize, that beginning in the early 19th century, everywhere but Morocco, where French authority emerges later, there will be regimes of European foreign rule.

And occupation and colonialism in North Africa-- and this is really very important as a bedrock for understanding the Second World War era-- colonialism comes with the ravaging of landscape, the theft of cultural treasure, restrictions on religious practice, restrictions on movement, enforced documentation of bodies, and certainly the deprivation of rights-- legal rights.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

So this comes to define a century-- from beginning to the Second World War era roughly-- a century of colonial authority in the region that affects every resident there. And the incursion of imperial powers, European imperial powers, in the region brings with it a population of European settler, colonialists who moved to the region.

It is a diverse population-- Sicilian, Italian, French, and more-- who are Christian, who come and settle in North Africa, who tend to disrupt communities of coexistence in the places they come to reside in. And often, are carrying with them theories of race and anti-Semitism and racism--

[MUSIC PLAYING]

--that they then mete out, not only on Jews, but on Muslims. But particularly, when it comes to Jewish history, this population, far more than the local Muslim population, is responsible through the beginning of the 20th century up until the Second World War era for inciting violence against Jews.

And often, in the perverse discourse of colonialism, pinning that violence on Muslim parties when, in fact, it is largely instigated by these Christian-- let's call them representatives of state, but they're not actually-- they don't tend to have power. They represent the state in so far as they come with a colonial incursion, and they are emboldened and sometimes financially incentivized to come to North Africa as settlers.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Along with Sarah just mentioned, you have certain figures from Europe that are also representing high authority. So you have Moses Montefiore's visit to Morocco meeting with the sultan of Morocco, and for instance, pushing them to change certain laws to more rights.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

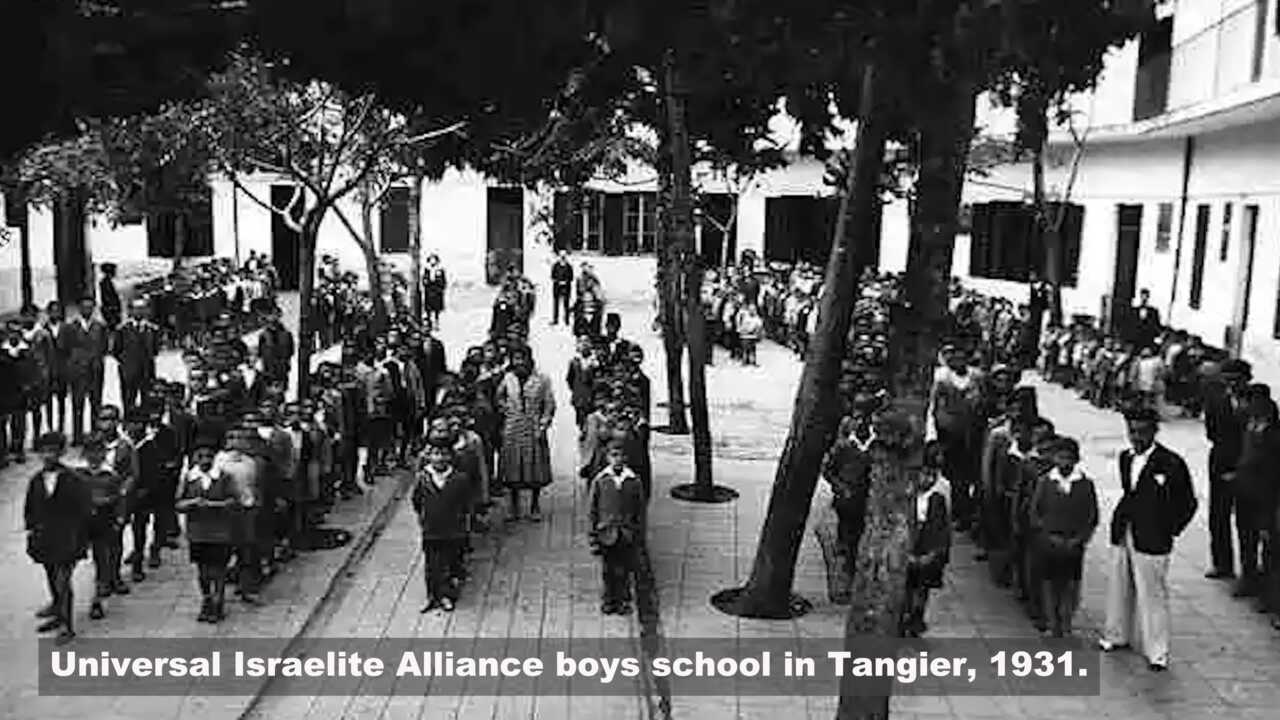

We have now the beginning of European Jews telling North African leaders to change status, legal status, of Jews to something different that fits the norms of what happened in Europe. You have in 1862, the establishment of the famous Alliance Israeli Universal, which is a system of schooling that would be funded and supported by the Jews of France, basically to modernize and to introduce the local Jewish communities to the modern era.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

We have now the beginning of what-- you have the colonial structures, but we have also other legal forms and other social and educational changes that follow that.

The colonial era and this rise of European Jewish philanthropic and pedagogical influence upon the Jews of North Africa rings, but also emerges in parallel with the rise, of a middle class in this region-- Jews, as well as Muslims. And among the Jewish community, some of those who rise to the middle class-- not all, but some-- do so because they are economic intermediaries between the colonial order.

Whether as merchants or as translators, these Jews represent a body of Jews who are entering the middle class, who are leaving traditional Jewish neighborhoods, especially across the coastal cities of Northern North Africa, leaving traditional Jewish neighborhoods for new bourgeois suburbs, let's call them.

And when the Second World War will strike, that means we have divided Jewish communities within individual cities of those Jews who are poorer, who remain within traditional Jewish neighborhoods, and those who have, whether willingly or opportunistically, or perhaps under a degree of duress, have embraced the adoption of the French language, sending their children to French schools, moving out of Jewish neighborhoods, sometimes giving their children newly gallicized or Frenchified names.

Now, historians debate, does this represent their loyalty to the French regime? Does it represent an embrace of colonialism and French culture? Or alternatively, does it represent a kind of local, creative response to what modernity looked like in North Africa?

I think we can put aside questions of judgment, and just point to the dramatic ways in which culture was shifting. And these Jews who participate in these shifts, alongside Jews who, for reasons of class or geographic location, are further from colonial authority represent new forms of division, but also cultural vivacity within North Africa's Jewish community.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

So one of the things I think we have to consider in our understanding of the experience of every community is that each region in North Africa went through a different historical moment of colonization.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

So you have Algeria was colonized in 1830, Tunisia in 1880s-- 1882, and Libya-- 1911, Morocco-- 1912. So that-- the fact that a country went from almost a century of colonization is different from a country we're going through. So those are important.

I would say whatever markers we can point to that suggests that there were certain Jews through their class status, or their job, or their political leanings, or their geography were affiliated with colonial authority in some way, we can also point to an infinite number of examples of how right up until the era of the Second World War, Jews continued to self-identify as local, as Indigenous, as sometimes in their own terminology, Arab, whether through their musical choice, whether through their poetry, their song, their liturgy, their politics, their social affinities in so many ways that our wonderful colleagues have helped us to understand.

Jews continue to be, broadly speaking, North African. Also, local-- of their town, of their region, of their community, not outsiders, no matter its slow gravitation in certain places and among certain populations towards European cultural norms.

It's still today-- if you go-- if you think about-- if you talk to Moroccan or North African Jews in general-- Tunisians, Algerian, Moroccans-- and where they-- they would first point to their villages or towns. Even here in LA or whatever, they would say, I'm from Fez, or I'm from Constantine before they say I'm Jewish.

And there is also an oral history, an oral culture around that, so in terms of language. So the language that people in Fez or in Tunis speak is different from the language that we speak in Marrakesh. And they would make fun of themselves. They would tease each other. They would fight sometimes, even in context of how each school of Judaism represents itself, whether it's from Fez or from-- City of Fez or from City of Meknes, for instance. So that's very important. Origin and place are also important.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Colonialism and the Jews of North Africa

You might also be interested in…

Developing Student Agency through History and Literature: Middle School Curriculum

Resources for Civic Education in California

Resources for Civic Education in Massachusetts

The Holocaust and North Africa: Resistance in the Camps

The Holocaust and Jewish Communities in Wartime North Africa

Pre-War Jewish Life in North Africa

Responses to Rising Antisemitism and Antisemitic Legislation in North Africa

10 Questions for the Past: The 1963 Chicago Public Schools Boycott

The Union As It Was

Radical Reconstruction and the Birth of Civil Rights

The Struggle over Women’s Rights

Equality for All