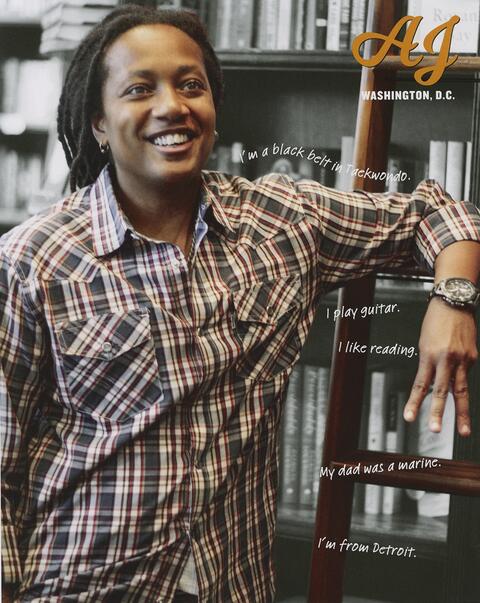

AJ from Washington, DC

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- English & Language Arts

- Culture & Identity

Growing up with Black parents in Detroit, race was as innate as breathing, but gender was more intellectual. I lived with a lot of male cousins. They played sports, and I played sports. They treated us all the same. So, my gender came to my consciousness later on, when I began recognizing how people saw me as I grew, and how that didn’t feel congruent with how I felt.

It started out as sexuality. I knew that everybody said that I’m a girl, so I must be a girl. Therefore, I came out as a lesbian. But I also knew it was something else that I didn’t want to share. I went all through high school without dating anybody, and people didn’t question me. My gender would come up often—like people would ask why I’m dressing neutrally or like a boy—but I just lumped it, like many people do, into my sexuality. 1 I’m aware that my gender is still not easily recognizable, and calling someone who looks like me “ma’am” is perfectly fine. I chose not to take the physical course of action to modify my body, because I am a singer. When you take the sex hormones, your voice is irreparable, and I love my voice. So I just modify my appearance to reflect “being male.”

Still, I have to be careful about how I respond. Getting “she-bombed” 2 all the time feels like a racial microaggression, and I have to get affirmation all the time. I understand why people get gender reassigned, because they want the way they feel and the way they look to match.

I have friends who are like, “call me they.” It was annoying because I had to change the sentence structure in my head before I said the sentence. Now, I’m feeling like “they” is pretty dope. “They” has always been around, even when I was not cognizant of the gender piece and it was just the sexuality piece. I was like, “Oh yeah, I’m dating someone. They are so cool,” when I didn’t want to come out to somebody. For people who are trans, it is not always this or that, male or female. It’s this other thing. I like that “they” managed to incorporate that duality.

You can’t control what people think. You can’t control how they see the world. You can’t control whether they see you as you want to be seen, but you are who you are. The biggest thing that I would say is, trust yourself. Trust who you are and always remember it. I still protect those pure aspects of that little boy growing up before he was told to be a girl. 3

- 1Gender identity is an internal knowledge of being male, female, or another gender, while sexual orientation is determined by the gender you are attracted to, regardless of whether or not you are transgender. A transgender woman was labeled as male at birth; if she is exclusively attracted to women, she is a lesbian transgender woman.

- 2Getting she-bombed means when people use the wrong gender pronouns, such as “she/her/hers” for AJ. To voice this, ask people what their preferred pronouns are. Self-identifying males typically take the pronouns “he/him/his,” and self-identifying females take “she/her/hers.” Gender-neutral or genderqueer pronouns are “they/them/their.” Some may take any and all pronouns, or ones unmentioned here. Genderqueer “people see gender not as binary with men or women, but as a spectrum that ranges from masculinity to femininity.”

- 3From Winona Guo and Priya Vulchi, Tell Me Who You Are: Sharing Our Stories of Race, Culture, and Identity (New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 2017), 160–162. Reproduced by permission of TarcherPerigee, an imprint of the Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.