The Power of Names

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

Grade

9–12Duration

One 50-min class period- Democracy & Civic Engagement

- Human & Civil Rights

- Racism

Overview

About This Lesson

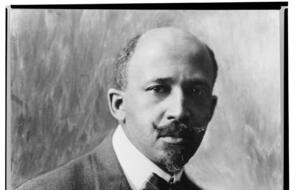

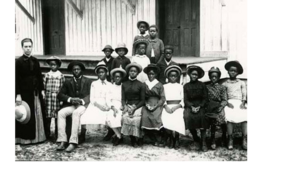

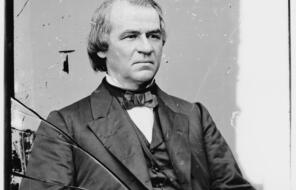

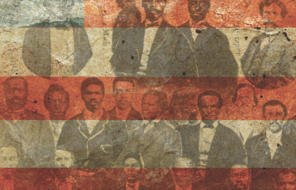

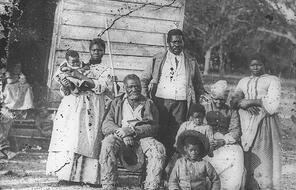

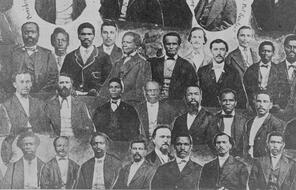

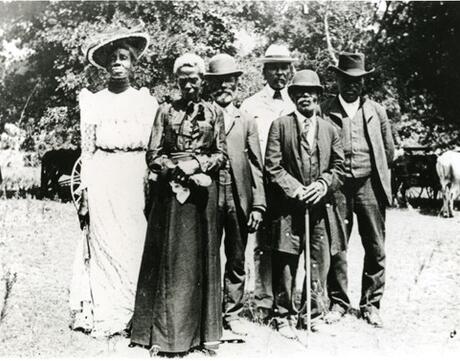

The era of Reconstruction that followed the US Civil War spawned debates—and significant violence—over issues that are intensely relevant in the lives of adolescents and particularly important for democracy: power, respect, fairness, equality, and the meaning of freedom, among others. At the heart of all of these issues is the relationship between the individual and society, a relationship worth exploring at the outset of a study of Reconstruction.

This lesson begins with an examination of one of the most basic forms of connection between the individual and society: names. “It is through names that we first place ourselves in the world,” writes Ralph Ellison. He goes on to say that as we act in the world around us, our names are simultaneously masks, shields, and containers of values and traditions. In this lesson, students will reflect on these three functions of names and explore the relationship between our names and our identities. They will consider the following questions:

- What do our names reveal about our identities? What do they hide?

- What do names suggest about the degree of freedom and agency we have in society?

- How can names bestow dignity and respect on individuals? How can they also be used to deprive individuals of those qualities?

- To what extent do we choose the names and labels others use for us? What parts of our identities do we choose for ourselves? What parts are chosen for us by others, or by society?

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before teaching this lesson, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Lesson Plans

Activities

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Download the Files

Get Files Via Google

The Power of Names

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand