Breadcrumb

- Video Witnessing Antisemitic Violence

- Video Changes at School under the Nazis

- Video From Democracy to Dictatorship

- Video Preparing for the Kindertransport

- Video Friendship and Betrayal

- Video Marched to the Ghetto

- Video Life or Death in the Netherlands

- Video Joining the Resistance

- Video Finding Safety in Italy

- Video Resistances in Auschwitz

- Video Turned Away on the M.S. St. Louis

- Video Warning the World

- Video Witness to a Massacre

- Video Eyewitness to Buchenwald

- Video Reconciling Identities after the War

- Video Caring for Survivors

- Video 1 The Red Army Enters Majdanek

Antisemitism after Liberation

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Antisemitism

- The Holocaust

Antisemitism after Liberation

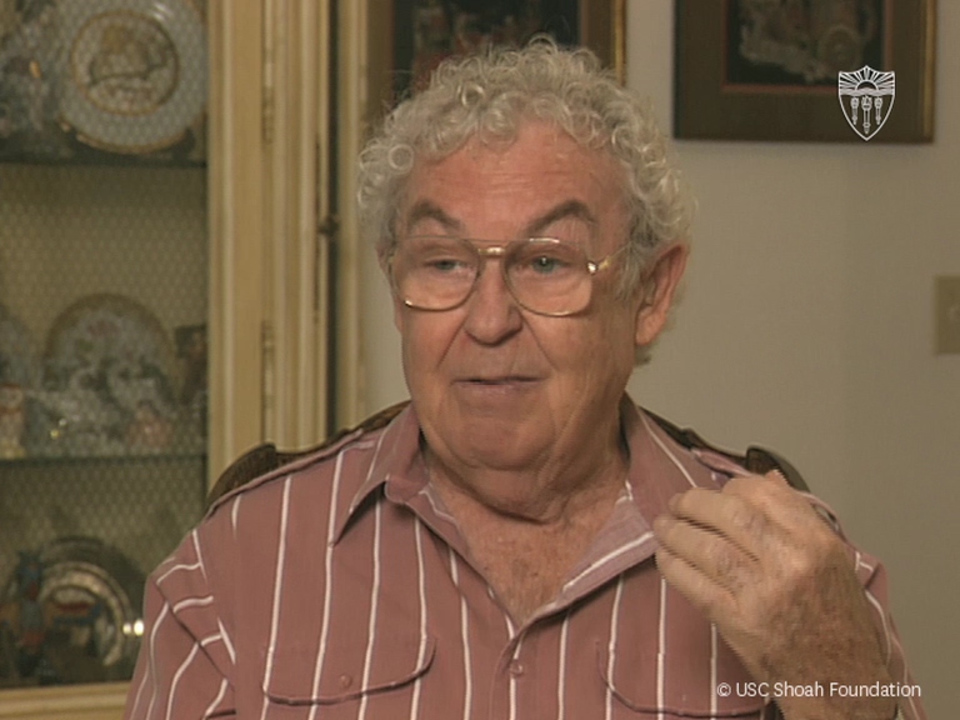

I came into contact with quite a bit of antisemitism. We had a mess sergeant, who at that time was the assistant mess sergeant, named Cooley. Cooley came from someplace-- I have it in my records-- either North Carolina or South Carolina or Georgia, in that area. And he was a racist to the roots, and he would call me Jew boy and kike. And on more than one occasion, we literally had to be separated, physically separated.

I think he actually could have almost erased me, but I made a vow to myself when I was a kid that never again would I accept that without fighting back, and that was my pattern.

Overseas, when we were no longer actually in combat, there was an opportunity or a situation where I literally came very close to and almost killed him for antisemitism. We had picked up some liberated displaced persons. They were wandering along the road, and they pleaded with us because they wanted to get back as close as they could to where they had last seen any of their relatives still alive.

And they would sew our uniforms, help the cooks, work on our vehicles, sew on patches-- whatever they could do for us, even cut hair, just so we would take them along as we traveled. I came home from a patrol one day with five or six other fellows, and we heard a large commotion in the camp area where we were. And we dropped our gear on the floor, on the ground, and went to see what was going on.

And I realized-- I heard Cooley's voice yelling, you dirty kike, blankety blank blank blank. You'll eat all of that, or I'll kill you. And I pushed my way through the crowd, and sitting on a box was this displaced person, Grisha. He had a large can of peanut butter that was open in his lap, big spoon in his hand. He had peanut butter smeared all over his face. And Cooley was screaming at him every invective imaginable.

It horrified me that anybody could-- whatever he was doing, whatever caused it didn't even matter. This was a man, a Jew, from a camp. And Cooley, the antisemite, was doing this to him. I walked over. I knocked the can out of Grisha's hand and pulled him to his feet and pushed him away.

And, of course, Cooley turned to me and screamed, what the hell do you think you're doing, you kike bastard? And I remember as I faced Cooley, I took my pistol from my belt, and holding it down at my side, I said, Cooley, if I ever see you treat another Jew like this again, I'll kill you. And I brought the hammer back. It sounded like a steel door being slammed. It was so quiet. The crowd around us didn't make a sound.

Cooley looked at me with disbelief, and he turned around and pushed his way out of the crowd. I've thought about that so very, very many times, and I swear to this day, I don't know had he stood up to me, what could have happened. I don't know if I could have or I would have-- I don't know.

But those days, we weren't human. I can't say we were living like animals because animals don't act that way. But the euphemism of being human and sane just didn't exist anymore. We weren't normal. We just weren't normal in those days. And whether I could have, I don't know. But Cooley never came near me again. He avoided me like the plague.

Antisemitism after Liberation

You might also be interested in…

Holocaust Trivialization and Distortion

The Holocaust and North Africa: Resistance in the Camps

Contextualizing a Found Poem

The Holocaust and Jewish Communities in Wartime North Africa

Pre-War Jewish Life in North Africa

Holocaust and Human Behavior: A Facing History & Ourselves High School Elective Course

Responses to Rising Antisemitism and Antisemitic Legislation in North Africa

Responding to Rising Antisemitism

Responding to the Synagogue Attack in Colleyville, Texas: For Jewish Educational Settings

Responding to the Synagogue Attack in Colleyville, Texas

Addressing Antisemitism Online

Understanding the Christian Roots of Antisemitism